I can just hear the advertisement now.

Do you have perfect pitch? Would you like to? Then Depakote might be right for you . . .

Perfect pitch is the ability to name or produce a musical note without a reference note. While most children presumably have the capacity to learn perfect pitch, only one in about ten thousand adults can actually do it. That’s because children must receive extensive musical training as youngsters to develop it. Most adults with perfect pitch began studying music at six years of age or younger. By the time children turn nine, their window to learn perfect pitch has already closed. They may yet blossom into wonderful musicians but they will never be able to count perfect pitch among their talents.

Or might they after all?

Well no, probably not. But a new study, published in Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, has opened the door to such questions. Its authors tested how young men learned to name notes when they were on or off of a drug called valproate (brand name: Depakote). Valproate is widely used to treat epilepsy and bipolar disorder. It’s part of a class of drugs called histone-deacetylase, or HDAC, inhibitors that fiddle with how DNA is stored and alter how genes are read out and translated into proteins.

The intricacies of how HDAC inhibitors affect gene expression and how those changes reduce seizures and mania are still up in the air. But while some scientists have been working those details out, others have been noticing that HDAC inhibitors help old mice learn new tricks. These drugs allow adult mice to adapt to visual and auditory changes in ways that are only otherwise possible for juvenile mice. In other words, HDAC inhibitors allowed mice to learn things beyond the typical window, or critical period, in which the brain is capable of that specific type of learning.

Judit Gervain, Allan Young, and the other authors of the current study set out to test whether HDAC inhibitors can reopen a learning window in humans as well. They randomly assigned their young male subjects to take valproate for either the first or the second half of the study. (Although I usually get my hackles up about the exclusion of female participants from biomedical studies, I understand their reason for doing so in this case. Valproate can cause severe birth defects. By testing men, the authors could be one hundred percent certain that their participants weren’t pregnant.) The subjects took valproate for one half of the study and a placebo for the other half . . . and of course they weren’t told which was which.

During the first half of the study, they trained twenty-four participants to learn six pitch classes. Instead of teaching them the formal names of these pitches in the twelve-tone musical system, they assigned proper names to each one (e.g., Eric, Rachel, or Francine), indicating that each is the name of a person who only plays one pitch class. The participants received this training online for up to ten minutes daily for seven days. During the second half of the study, eighteen of the same subjects underwent the same training with six new pitch classes and names. At the end of each seven-day training session, they heard the six pitch classes one at a time and, for each, answered the question: “Who played that note?”

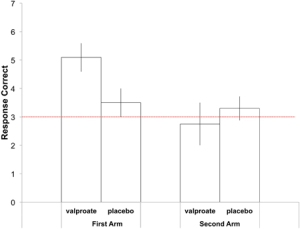

Study results showing better performance at naming tones for participants on valproate in the first half of the experiment. From: Gervain et al, 2013

The results? There was a whopping effect of treatment on performance in the first half of the study. The young men on valproate did significantly better than the men on placebo. That’s pretty cool and amazing. It is particularly impressive and surprising because the participants received very little training. The online training summed to a mere seventy minutes and some of the participants didn’t even complete all seven of the ten-minute sessions.

As cool as the main finding is, there are some odd aspects to the study. As you can see from the figure, the second half of the experiment (after the treatments were switched) doesn’t show the same result as the first. Here, participants on valproate perform no differently from those on placebo. The authors suggest that the training in the first half of the experiment interfered with learning in the second half – a plausible explanation (and one they might have predicted in advance). Still, at this point we can’t tell if we are looking at a case of proactive interference or a failure to replicate results. Only time and future experiments will tell.

There were two other odd aspects of the study that caught my eye. The authors used synthesized piano tones instead of pure tones because the former has additional cues like timbre that help people without perfect pitch complete the task. They also taught the participants to associate each note with the name of the person who supposedly plays it rather than the name of the actual note or some abstract stand-in identifier. Both choices make it easier for the participants to perform well on the task but call into question how similar the participants’ learning is to the specific phenomenon of perfect pitch. Perhaps the subjects on valproate in the first half of the experiment were relying on different cues (e.g., timbre instead of frequency). Likewise, associating proper names of people with notes may help subjects learn precisely because it recruits social processes and networks that people with perfect pitch don’t use for the task. If these social processes don’t have a critical period like perfect pitch judgment does, well then valproate might be boosting a very different kind of learning.

As the authors themselves point out, this small study is merely a “proof-of-concept,” albeit a dramatic one. It is not meant to be the final word on the subject. Still, I am curious to see where this leads. Might valproate’s success with seizures and mania have something to do with its ability to trigger new learning? And if HDAC inhibitors do alter the brain’s ability to learn skills that are typically crystallized by adulthood, how has that affected the millions of adults who have been taking these drugs for years? Yet again, only time and science will tell.

I, for one, will be waiting to hear what they have to say.

_______

Photo credit: Brandon Giesbrecht on Flickr, used via Creative Commons license

Gervain J, Vines BW, Chen LM, Seo RJ, Hensch TK, Werker JF, & Young AH (2013). Valproate reopens critical-period learning of absolute pitch. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 7 PMID: 24348349