It is both amusing and enlightening to hear my 21-month-old daughter sing the alphabet song. The song is her favorite, though she is years from grasping how symbols represent sound, not to mention the concept of alphabetical order. Still, if you start singing the song she will chime in. Before you think that’s impressive, keep in mind that her version of the song is more or less this: “CD . . . G . . . I . . . No P . . . S . . . V . . . Dub X . . . Z.”

Her alphabet song adds up to little more than a Scrabble hand, yet it is a surprising feat of memory all the same. My daughter doesn’t know her last name, can’t read or write, and has been known to mistake stickers for food. It turns out that her memory for the alphabet has far less to do with letters than lyrics. From Wheels on the Bus to Don’t Stop Believin’, she sings along to all of her favorite songs, piping up with every word and vowel she remembers. Her performance has nothing to do with comprehension; she has never seen or heard about a locker, yet she sings the word at just the right time in her rendition of the Glee song Loser like Me. (Go ahead and judge me. I judge myself.)

My daughter’s knack for learning lyrics is not unique to her or to toddlers in general. Adults are also far better at remembering words set to song than other strings of verbal material. That’s why college students have used music to memorize subjects from human anatomy to U.S. presidents. It’s why advertisers inundate you with catchy snippets of song. Who can forget a good jingle? To this day, I remember the phone number for a carpet company I saw advertised decades ago.

But what is it about music that helps us remember? And how does it work?

It turns out that rhythm, rather than melody, is the crucial component to remembering lyrics. In a 2008 study, subjects remembered unfamiliar lyrics far better if they heard them sung to a familiar melody (Scarborough Fair) than if they heard them sung to an unfamiliar song or merely spoken without music. But they remembered the lyrics better still if they heard the lines spoken to a rhythmic drummed arrangement of Scarborough Fair. Even an unfamiliar drummed rhythm boosted later memory for the words. By why should any of these conditions improve memory? According to the prevailing theory, lyrics have a structural framework that helps you learn and recall them. They are set to a particular melody through a process called textsetting that matches the natural beat and meter of the music and words. Composers, lyricists, and musicians do this by aligning the stressed syllables of words with strong beats in the music as much as possible. Music is also comprised of musical phrases; lyrics naturally break down into lines, or “chunks,” based on these phrase boundaries. And just in case you missed those boundaries, lyricists often emphasize the ends of these lines with a rhyming scheme.

Rhythm, along with rhyme and chunking, may be enough to explain the human knack for learning lyrics. Let’s say you begin singing that old classic, Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. You make it to “How I wonder,” but what’s next? Since the meter of the song is BUM bah BUM bah and you ended on bah, you know that the next words must have the stress pattern BUM bah. This helps limit your mental search for these words. (Oh yeah: WHAT you!) The final word in the line is a breeze, as it has to rhyme with “star.” And there you have it. Rhythm, along with rhyme and chunking, provide a sturdy scaffold for your memory of words.

For a more personal example of rhythm and memory, consider your own experience when you remember the alphabet. It’s worth noting that the alphabet song is set to a familiar melody (the same as Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star and Baa, Baa, Black Sheep), a fact that surely helped you learn the alphabet lyrics in the first place. Now that you know them, ask yourself this: which comes first, the letter O or L? If you’re like me, you have to mentally run through the first half of the song to figure it out. Yet this mental rendition lacks a melody. Instead, you list the letters according to the song’s rhythm. Your list probably pauses after G and again after P and V, which each mark the end of a line in the song. The letters L, M, N, and O each last half as long as the average letter, while S sprawls out across twice the average. Centuries ago, a musician managed to squeeze the letters of the alphabet into the rhythm of an old French folk song. Today, the idiosyncratic pairing he devised remains alive – not just in kindergarten classrooms, but in the recesses of your brain. Its longevity, across generations and across the lifespan, illustrates how word and beat can be entwined in human memory.

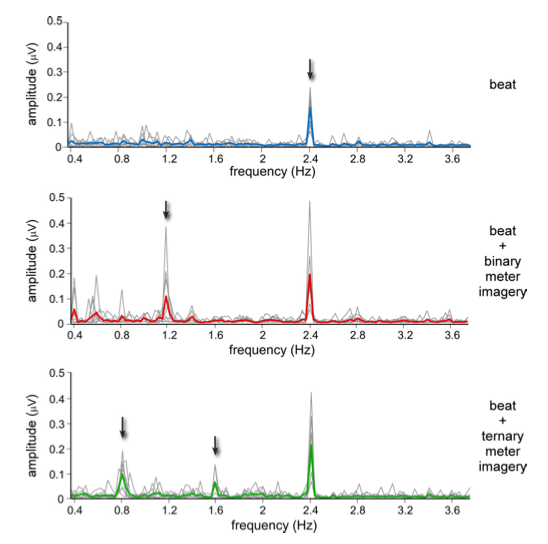

While a rhythm-and-rhyme framework could explain the human aptitude for learning lyrics, there may be more to the story. As a 2011 study published in the Journal of Neuroscience shows, beat and meter have special representations in the brain. Participants in the study listened to a pure tone with brief beats at a rate of 144 per minute, or 2.4 Hz. Some of the participants were told to imagine one of two meters on top of the beat: either a binary meter (a march: BUM bah BUM bah BUM) or a ternary meter (a waltz: BUM bah bah BUM bah bah BUM). These meters divided the interval between beats into two or three evenly spaced intervals, respectively. A third group performed a control task that ensured subjects were paying attention to the sound without imagining a meter. All the while, the scientists recorded traces of neural activity that could be detected at the scalp with EEG.

The results were remarkable. Brain waves synchronized with the audible beat and with the imagined meters. This figure from the paper shows the combined and averaged data from the three experimental groups. The subjects in the control group (blue) heard the beat without imagining a meter; their EEGs showed strong brain waves at the frequency of the beat, 2.4 Hz. Both the march (red) and waltz (green) groups showed this 2.4 Hz rhythm plus increased brain waves at the frequency of their imagined meters (1.2 Hz and 0.8 Hz, respectively). The waltz group also showed another small peak of waves at 1.6 Hz, or twice the frequency of their imagined meter, a curiosity that may have as much to do with the mechanics of brain waves as the perception of meter and beat.

In essence, these results show that beat and meter have a profound effect on the brain. They alter the waves of activity that are constantly circulating through your brain, but more remarkably, they do so in a way that syncs activity with sound (be it real or imagined). This phenomenon, called neural entrainment, may help you perceive rhythm by making you more receptive to sounds at the very moment when the next beat is due. It can also be a powerful tool for learning and memory. So far, only one group has tried to link brain waves to the benefits of learning words with music. Their papers have been flawed and inconclusive. Hopefully some intrepid scientist will forge ahead with this line of research. Until then, stay tuned. (Or should I say metered?)

In essence, these results show that beat and meter have a profound effect on the brain. They alter the waves of activity that are constantly circulating through your brain, but more remarkably, they do so in a way that syncs activity with sound (be it real or imagined). This phenomenon, called neural entrainment, may help you perceive rhythm by making you more receptive to sounds at the very moment when the next beat is due. It can also be a powerful tool for learning and memory. So far, only one group has tried to link brain waves to the benefits of learning words with music. Their papers have been flawed and inconclusive. Hopefully some intrepid scientist will forge ahead with this line of research. Until then, stay tuned. (Or should I say metered?)

Whatever the ultimate explanation, the cozy relationship between rhythm and memory may have left its mark on our cultural inheritance. Poetry predated the written word and once served the purpose of conveying epic tales across distances and generations. Singer-poets had to memorize a harrowing amount of verbal material. (Just imagine: the Iliad and Odyssey began as oral recitations and were only written down centuries later.) Scholars think poetic conventions like meter and rhyme arose out of necessity; how else could a person remember hours of text? The conventions persisted in poetry, song, and theater even after the written word became more widespread. No one can say why. But whatever the reason, Shakespeare’s actors would have learned their lines more quickly because of his clever rhymes and iambic pentameter. Mozart’s opera stars would have learned their libretti more easily because of his remarkable music. And centuries later you can sing along to Cyndi Lauper or locate Fifty Shades of Grey in the library stacks – all thanks to the rhythms of music and speech.

__________

Photo credits: David Martyn Hunt on Flickr and Nozaradan, Peretz, Missal & Mouraux via The Journal of Neuroscience

Nozaradan, S., Peretz, I., Missal, M., & Mouraux, A. (2011). Tagging the Neuronal Entrainment to Beat and Meter The Journal of Neuroscience DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0411-11.2011