One of the new picture books making the bedtime rounds at our house is How Do Dinosaurs Say Goodnight?, which describes and depicts dinosaurs doing such un-dinosaurly things as tucking themselves into bed or kissing their human mothers good night. The book is whimsical, gorgeously illustrated, and includes a scientific angle, as the genus names of the dinosaurs are included in the pictures. I’m always careful to read these genus names aloud as we look at each picture. But is this book actually teaching my daughter anything about dinosaurs? And does the misinformation get in the way of her learning these facts? A new study suggests that it might.

Picture books that anthropomorphize animals – and even inanimate objects – are the norm rather than the exception. These books are whimsical and fanciful. They depict worlds like our own but different in magical ways that delight children and adults alike. Perhaps these books are more engaging for young children, fostering lifelong reading habits. Perhaps they stimulate a child’s blossoming imagination. Perhaps – although I would argue that the true story of our diverse, teeming planet is more remarkable than talking teddy bears or hippos in swimsuits.

Look at it this way: everything we do is meant to prepare our children for life in this complex and befuddling world. Why, then, do we feed them so much distorted, inaccurate information? How are they supposed to know what is real and what is fantasy? How is my daughter supposed to know that the three-horned dinosaur was called Triceratops but that it never coexisted with humans nor stomped on its hind legs to protest bedtime?

Researchers in Boston and Toronto looked into this issue and recently published their findings in Frontiers in Psychology. The scientists created picture books based on three animals species that are relatively unknown among North American children: cavies, oxpeckers, and handfish. Their study consisted of two separate experiments. For the first experiment, all of the books featured factual illustrations of the animals, but for each animal the authors made one version of the book with realistic text and one version with text that depicted the animals as human-like. Here are two examples:

Lonely cavy seeks companionship and good conversation.

Realistic

When the mother cavy wakes up, she usually eats lots of grass and other plants.

Then the mother cavy feeds her baby cavies.

Mother cavy also licks the babies’ fur to keep them clean.

Mother cavy and her babies spend the rest of the day lying in the sun.

At night, they sleep in a small cave.

After they go to sleep, mother cavy’s big ears help her hear noises around her.Anthropomorphic

“Yum, those grass and plants are delicious!” Mother cavy thinks as she eats her breakfast.

“I will feed some to my baby cavies too!” she says.

The baby cavies love to play in the grass! But they’ve gotten all dirty! “Time for your bath,” Mother cavy says.

Mother cavy and her babies like to spend the afternoon sunbathing.

At night, Mother cavy tucks her babies in to bed in a small cave. “Mom, I’m scared!” says the baby cavy.

“Don’t be afraid,” she says. “I’ll listen for noises with my big ears and keep us safe.”

Children ages 3 to 5 years old were randomly assigned to read the books with either the factual or fantasy text. After children read one of these books with an experimenter, a second experimenter showed them a picture of the real animal described the story and asked the kids questions about it. Do cavies eat grass? Do cavies talk? Some of these questions tested the factual information kids took away from the picture book, while others tested how much the children anthropomorphized the animal. The children who read the books with talking animals were more likely to say those animals really talk than were children who read the versions with factual text. Still, the two groups were roughly equal in the factual information they retained about the animals.

Oxpeckers ready for adventure.

For the second experiment, the researchers again made two versions of picture books for each animal. This time, both versions showed the animals dressed in clothes, sitting at tables, or engaged in other human activities. As before, the researchers made two versions of each book: one with factual text and one that anthropomorphized the animals. The children who read the fully anthropomorphized picture books tended to believe that the animals really engage in human behaviors like speech. These kids also answered fewer factual questions about the animals correctly (compared with the children who read factual text paired with the fantastical pictures).

These findings have two major implications. First, picture books that anthropomorphize animals seem to actually teach children that animals think and behave like humans. In one sense you might say this is good, as it could discourage animal cruelty and abuse. But in another sense, it’s highly unproductive. At the very best, children will have to unlearn all of this nonsense. At worst, they will carry some of this misinformation about the natural world throughout life – probably not as a belief in talking animals, but in the assumptions they make about the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of other species.

The other takeaway is that the whimsical aspects of a picture book may be sabotaging your child’s learning of the real information in these stories, particularly when the illustrations and text both reflect fantasy. Since children can’t conclusively tell fact from fiction, some may be discounting all information from highly fanciful stories – including incredible-yet-true facts like the chameleon’s mercurial skin tone or the transformation of caterpillar into butterfly. As the authors write in their paper: “if the goal of the picture book interaction is to teach children information about the world, it is best to use books that depict the world in a realistic rather than fantastical manner.” Of course that takes enthusiasm out of the equation. What kid would sit for hours watching videos of real trains when he or she could watch Thomas? Human narrative adds interest, but it also seems to muddle up real learning, at least in preschoolers.

I hate to build an argument against imaginative, fanciful picture books. What am I, Scrooge? But while I love imagination, I don’t love misinformation – particularly scientific misinformation. And while I love magic, I don’t love magical thinking or flawed reasoning about the natural world. I’m not saying you should throw away your copy of Goodnight Moon and all things Sandra Boynton – just keep in mind that wee ones don’t always know real from fanciful or facetious. Talk about these concepts with them. Buy some nonfiction picture books with accurate information about animals and keep them in the lineup. And know that, for all your efforts, they may come away believing that trains talk and bunnies knit . . . at least for now.

_____

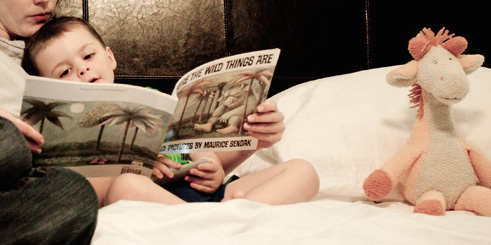

Photo credits: Mother and child by KatLevPhoto, cropped for use here; cavy by Brent Moore; oxpeckers by Steve Garvie. All used via Creative Commons license

Ganea, P., Canfield, C., Simons Ghafari, K., & Chou, T. (2014). Do cavies talk? The effect of anthropomorphic picture books on children’s knowledge about animals Frontiers in Psychology, 5 DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00283

I have a different idea about the anthropomorphized books than you do. It depends on what your rationale is for reading to and with your kids. If your main goal is the sharing of information then I think you’re partly correct. Probably not the best way to teach them about new things – though the studies you cited didn’t seem to include one vital variable, which is the fact that parents are usually reading the books to kids and can help to clarify what’s real from what’s not real.

To me, there’s another major reason to read book likes that to kids. That is, it can show them that there are few if any boundaries to people’s imaginations. You can be as creative as you want. If you want to write a story about a cat who wears a hat and comes to visit two kids and makes a mess of their house, you can do that. If you want to write a story about a curious monkey who gets into all sorts of trouble but then saves the day, you can do that.

Using animals in stories in fantastic or creative ways is a great way to get kids engaged in the stories that you’re telling and connected to whatever the lesson of that story might be. And if there’s no lesson, then it can be a great example of the scope of imagination. But if you want to teach them specific, true information, you’re probably right. Best to stick close to reality.

You are absolutely right – there are different benefits for different types of books. I read fantastical stories to my daughter because she loves them and I want her to love reading and make it a lifelong habit. But I think it’s interesting that so many of her books try to educate through fantasy. We figure that kids know which is which, and it’s worth revisiting those assumptions.

Thanks for reading and sharing your thoughts. Always great to hear from you!

Gotcha – but as long as you’re reading with her, you can say something like “Now, do you think that rabbits are REALLY able to talk to each other like that?” That way you can correct the misconceptions. But again, there are benefits to the less fantastical as well. Your daughter’s got something better than a good, non-fantastical book to help her learn. She’s got a curious, smart, caring mom who can help her discover new things.

Love reading your stuff, Rebecca. Keep ’em coming!

Pingback: ScienceSeeker Editors’ Selections: April 13 – 19, 2014 | ScienceSeeker Blog

How could anyone be angry about a post that shows a mother and child enjoying Where The Wild Things Are!?! Long live fantasy AND science AND loving parents that share both with their children!