Do you rely on your spouse to remember special events and travel plans? Your coworker to remember how to submit some frustrating form? Your cell phone to store every phone number you’ll ever need? Yeah, me too. You might call this time saving or delegating, but if you were a fancy psychologist you’d call it transactive memory.

Transactive memory is a wonderful concept. There’s too much information in this world to know and remember. Why not store some of it in “the cloud” that is your partner or coworker’s brain or in “the cloud” itself, whatever and wherever that is? The idea of transactive memory came from the innovative psychologist Daniel Wegner, most recently of Harvard, who passed away in July of this year. Wegner proposed the idea in the mid-80s and framed it in terms of the “intimate dyad” – spouses or other close couples who know each other very well over a long period of time.

Transactive memory between partners can be a straightforward case of cognitive outsourcing. I remember monthly expenses and you remember family birthdays. But it can also be a subtler and more interactive process. For example, one spouse remembers why you chose to honeymoon at Waikiki and the other remembers which hotel you stayed in. If the partners try to recall their honeymoon together, they can produce a far richer description of the experience than if they were to try separately.

Here’s an example from a recent conversation with my husband. It began when my husband mentioned that a Red Sox player once asked me out.

“Never happened,” I told him. And it hadn’t. But he insisted.

“You know, years ago. You went out on a date or something?”

“Nope.” But clearly he was thinking of something specific.

I thought really hard until a shred of a recollection came to me. “I’ve never met a Red Sox player, but I once met a guy who was called up from the farm team.”

My husband nodded. “That guy.”

But what interaction did we have? I met the guy nine years ago, not long before I met my husband. What were the circumstances? Finally, I began to remember. It wasn’t actually a date. We’d gone bowling with mutual friends and formed teams. The guy – a pitcher – was intensely competitive and I was the worst bowler there. He was annoyed that I was ruining our team score and I was annoyed that he was taking it all so seriously. I’d even come away from the experience with a lesson: never play games with competitive athletes.

Apparently, I’d told the anecdote to my husband after we met and he remembered a nugget of the story. Even though all of the key details from that night were buried somewhere in my brain, I’m quite sure that I would never have remembered them again if not for my husband’s prompts. This is a facet of transactive memory, one that Wegner called interactive cueing.

In a sense, transactive memory is a major benefit of having long-term relationships. Sharing memory, whether with a partner, parent, or friend, allows you to index or back up some of that memory. This fact also underscores just how much you lose when a loved one passes away. When you lose a spouse, a parent, a sibling, you are also losing part of yourself and the shared memory you have with that person. After I lost my father, I noticed this strange additional loss. I caught myself wondering when I’d stopped writing stories on his old typewriter. I realized I’d forgotten parts of the fanciful stories he used to tell me on long drives. I wished I could ask him to fill in the blanks, but of course it was too late.

Memories can be shared with people, but they can also be shared with things. If you write in a diary, you are storing details about current experiences that you can access later in life. No spouse required. You also upload memories and information to your technological gadgets. If you store phone numbers in your cell phone and use bookmarks and autocomplete tools in your browser, you are engaging in transactive memory. You are able to do more while remembering less. It’s efficient, convenient, and downright necessary in today’s world of proliferating numbers, websites, and passwords.

In 2011, a Science paper described how people create transactive memory with online search engines. The study, authored by Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu, and Wegner, received plenty of attention at the time, including here and here.

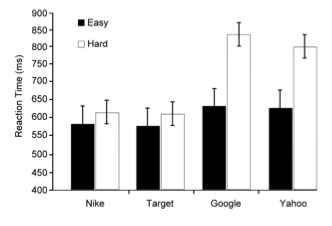

In one experiment, they asked participants either hard or easy questions and then had them do a modified Stroop task that involved reporting the physical color of a written word rather than naming the word. This was a measure of priming, essentially whether a participant has been thinking about that word or similar concepts recently. Sometimes the participants were tested with the names of online search engines (Google, Yahoo) and at others they were tested with other name brands (Nike, Target). After hard questions, the participants took much longer to do the Stroop task with Google and Yahoo than with the other brand names, suggesting that hard questions made them automatically think about searching the Internet for the answer.

The other experiments described in the paper showed that people are less likely to remember trivia if they believe they will be able to look it up later. When participants thought that items of trivia were saved somewhere on a computer, they were also more likely to remember where the items were saved than they were to remember the actual trivia items themselves. Together, the study’s findings suggest that people actively outsource memory to their computers and to the Internet. This will come as no surprise to those of us who can’t remember a single phone number offhand, don’t know how to get around without the GPS, and hop on our smartphones to answer the simplest of questions.

Search engines, computer atlases, and online databases are remarkable things. In a sense, we’d be crazy not to make use of them. But here’s the rub: the Internet is jam-packed with misinformation or near-miss information. Anti-vaxxers, creationists, global warming deniers: you can find them all on the web. And when people want the definitive answer, they almost always find themselves at Wikipedia. While Wikipedia has valuable information, it is not written and curated by experts. It is not always the God’s-honest-truth and it is not a safe replacement for learning and knowing information ourselves. Of course, the memories of our loved ones aren’t foolproof either, but at least they don’t carry the aura of authority that comes with a list of citations.

Speaking of which. There is now a Wikipedia page for “The Google Effect” that is based on the 2011 Science article. A banner across the top shows an open book featuring a large question mark and the following warning: “This article relies largely or entirely upon a single source. . . . Please help improve this article by introducing citations to additional sources.” The citation for the first section is a dead link. The last section has two placeholders for citations, but in lieu of numbers they say, According to whom?

Folks, if that ain’t a reminder to be wary of the outsourcing your brain to Google and Wikipedia, I don’t know what is.

_________

Photo credits:

1. Photo by Mike Baird on Flickr, used via Creative Commons license

2. Figure from “Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips” by Betsy Sparrow, Jenny Liu, and Daniel M. Wegner.

Sparrow B, Liu J, & Wegner DM (2011). Google effects on memory: cognitive consequences of having information at our fingertips. Science (New York, N.Y.), 333 (6043), 776-8 PMID: 21764755

OCTOBER, 1889. Scientists flocked to Berlin for the annual meeting of the German Anatomical Society. The roster read like a who’s who of famous scientists of the day.

OCTOBER, 1889. Scientists flocked to Berlin for the annual meeting of the German Anatomical Society. The roster read like a who’s who of famous scientists of the day.

Humans learn about objects by exploring them. I

Humans learn about objects by exploring them. I

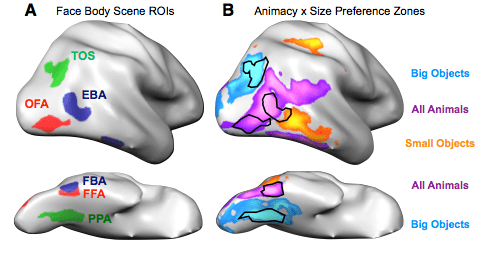

While we have five wonderful senses, humans rely most on our sense of sight. The allocation of real estate in the brain reflects this hegemony; a far greater chunk of your cerebral cortex is dedicated to vision than to any other sense. So when you encounter people, objects, and animals in the world, you typically use visual information to tell your lover from a toothbrush from your cat. And while it would be reasonable to expect your brain to process all of these items in the same way, it does nothing of the sort. Instead, the visual cortex segregates and plays favorites.

While we have five wonderful senses, humans rely most on our sense of sight. The allocation of real estate in the brain reflects this hegemony; a far greater chunk of your cerebral cortex is dedicated to vision than to any other sense. So when you encounter people, objects, and animals in the world, you typically use visual information to tell your lover from a toothbrush from your cat. And while it would be reasonable to expect your brain to process all of these items in the same way, it does nothing of the sort. Instead, the visual cortex segregates and plays favorites.